In this article I use the words “librism” and “librist” as direct borrows from the French “librisme” and “libriste”. You can define librism as a conjunction of the free software and free culture movements. I prefer to define it as the fringe of the anticapitalist struggles that strives to destroy intellectual property by creating new intangible commons and protecting them.

The following is a translation of an interview published in the February 2023 issue of Alternative Libertaire. I conducted this interview with the goal of offering to its readers a glimpse of what the free culture movement is. The magazine doesn’t target free software or free culture enthusiasts, and its printed edition constrains the size of its content. Please excuse the resulting briefness and simplifications.

Thanks to Nina for proofreading the translation.

Making comics, deciding to give up copyright and hoping to make a living from them in capitalist lands, what an idea! Yet that’s what the comic artist and librist activist David Revoy decided to do. Here’s a look at his unusual journey into the commons.

Alternative Libertaire: Hi David, your main work follows the adventures of the young witch Pepper and her cat Carrot, and you distribute your works under free licenses. What led you to make your work part of the commons?

David Revoy: At first, I was afraid of free licenses, I was afraid that one of my characters would be copied, that my style would be imitated, that I would have no control over it.

In the years 2009–2010, I worked for the Blender Foundation, the Creative Commons was mandatory and under their wing, it reassured me. I made concept-arts and it went well, I saw beautiful derivations, fan-arts and I didn’t see any unpleasant derivation, it reassured me a lot. I even saw the beneficial effects on propagation, audience and interest. There was an added value, it became a common good, a sandbox that other creators could use.

When I did my own comic book project, Pepper & Carrot, the commons imposed itslef to me as evident.

David Revoy is a French comic book author, publishing all its work under a free license

A community collaborates in the creation of you universes, how is it integrated into the creative process?

It’s not completely integrated, I’m using a software forge to create my collaborative space which is abused as a forum, and we have an instant messenging tool on the side. I made a special scenario forge, where people can publish their Pepper & Carrot scenarios under a free license, to check if it can inspire me to make an episode. But you can’t improvise yourself a scenarist, and I have a lot of scripts that start out with very good ideas but fail to come up with a ending or a plot-twist. So there’s a lot of fragments of ideas that I sometimes pick up, some published episodes are inspired by things that have been suggested to me.

What really happens in terms of collaboration is feedback. I share my story-board and the community will show me things that could be avoided, like a proofreading before publication. For example, two panels didn’t flow well and we couldn’t understand why the character comes from the right and then from the left, or why there was a bubble that said that at this particular moment. It allows me to anticipate these questions and to know if they are desired or if it is uncontrolled, if something is not understandable.

After that, the collaborative space is mostly around translation, there are now sixty languages and about a hundred people gravitating around the project, around twenty of which are active.

How do you manage to make a living from your art while giving up on the usual models?

Since all my work is under a free license and accessible without any pay wall, to make an economic model around it, there are not 3 000 solutions, there is only donation, voluntary patronage of the readers. Only a small percentage of the readership will contribute to the author’s livelihood by making a donation for the next episode that I publish every two months.

Home page of www.peppercarrot.com

When I made Pepper & Carrot in 2014, asking money like that was really frowned upon, for web-comics it was donations on Paypal and e-shops, one-time donations, but not recurring donations. Now it’s much more commonplace and almost every starting artist has a system for recurring donations, this system has spread a lot.

Since 2016, Pepper & Carrot is published by Glénat in print edition. Did you approach them or did they come to you after the online success of Pepper & Carrot?

Glénat clearly came to me after the online success of the comic, the publishing house was looking for web-comics authors and they contacted me to edit Pepper & Carrot. I was offered the classic contract following their process, with the standard contract from their legal department. They are the ones who have leverage on the author; unless you already make a lot of sales, when you are a very small author, you don’t tend to negotiate too much.

Except I told them that this would not be the concept at all, that there was the free tool, the free culture, and that I had no interest in the exclusivity system. They were convinced by the unusual concept that now serves as an experiment. We just signed the Creative Commons together. It bothered the legal department a bit because it’s not their usual process and they know that a competing publisher like Delcourt could publish Pepper & Carrot, it would be completely legal.

Glénat pays me when I release a new comic, as patronage, and I have no copyright on the books. When I do signings, whether I sell a million copies or zero, I don’t make any money, but I help Glénat to help me in return. Besides, I love signing books and I can’t sign web-comics, there’s a kind of synergy, we have a relationship based on trust.

Last October, you shared your irritation when you discovered the Bulgarian edition removed a lesbian relationship from the story. If the license gives them this right, how do you reconcile the desire to create commons and to preserve your story?

We had a full range of legal resources at our disposal, the Creative Commons doesn’t remove moral right, so if this edition put a red cross on the lesbian kiss panel, it would have been an opinion expressed to say “this is bad” and there I could have expressed my moral right and sued over it, because it is not what I want to express as an author. The fact that it removes the panel from the story doesn’t mean that the author is against it, because it doesn’t take anything away from the story. There’s an omission because the editor didn’t want to be persona non grata in the media for defending an opinion too progressive for his country.

I couldn’t use my moral rights on it, it’s annoying but there was a movement of readers who organized themselves to print the panel and glue it back into their album, it became a sign of militancy to patch the printed book.

You also promote the freely licensed tools you use, like the Krita drawing software. What do you gain by using these instead of proprietary tools like Photoshop?

Mostly freedom. Not the freedom to not pay because I have a support subscription on Krita equal to what Photoshop costs, but I can install it on as many machines as I want, use it in a computer room, and tell everyone “we’re doing a Krita workshop, install it”.

I’ve been helping the Krita project since 2010 by giving feedback, and I had a lot of adjustments made for my needs. Krita has become tailored to my drawing technique, I have all my reflexes catered for, it is the ultimate comfort. Secondly, I’m sure there is no telemetry. I can’t read Krita’s code, but I know that there’s a whole community who does and can assure me that at no moment in time there can be a line of code able to find out which documents I’m using, what tablet, how much time I’m spending on my drawing. It guarantees my privacy and ensures that I don’t have any ad.

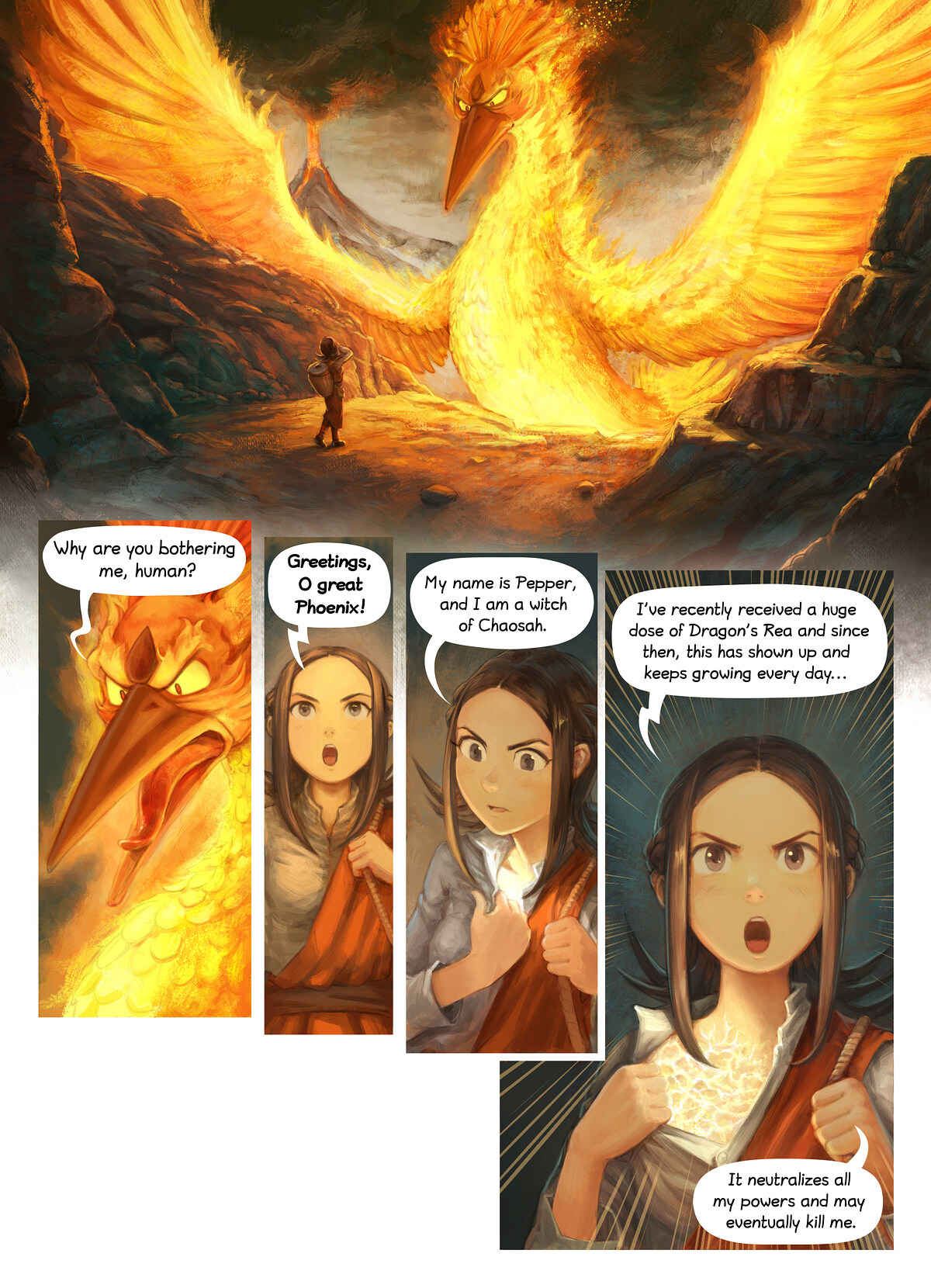

Illustration taken from the 37th episode of “Pepper & Carrot”, David Revoy, 2022

If tomorrow Adobe is bought by a billionaire, people who use Photoshop have no recourse. On Krita, there’s the Krita Foundation that develops it, but if they stop, its free license requires that the code has to be published somewhere and accessible. There will certainly be another group, or even myself, who will continue to build Krita and use it. This ensures that I can still benefit from my level and practice of drawing in the years to come, a guarantee that a Photoshp user would never get.

You also participate in the promotion of free software and free culture by illustrating many Framasoft campaigns. What political significance do you see in librism?

I see it as an online sandbox where you can try your hand at collaboration. You can try out a pyramidal structure with a leader, or a horizontal structure with each person being here on their own initiative, wanting to develop the project and to know how it works. I think this sandbox will allow us to develop reflexes of appreciation for certain models that will make us adopt certain policies instead retrospectively.

I don’t really believe in someone who will come up with a ready-made policy. School is not made like that, hobbies in France are not made like that, we always have a master on a podium, and now, all of a sudden, we’re going to be able to really have a space for experimentation of what collaboration is. I’ve already seen in librist festivals, when you have to pack up, how people organize themselves. That’s where free software has a great political force: to train people to collaborate.